The Wreck of HMS Whiting

Last Orders

Lieutenant John Jackson R.N. took command of HMS Whiting at Plymouth.

HMS Whiting’s final orders were issued to Lt. Jackson by Captain John Pasco, who as a Flag Lieutenant was the author of Admiral Lord Nelson’s famous message to his fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805: 'England Expects That Everyman Will Do His Duty'.

The last orders of the Whiting were:

By John Pasco Esqr Captain

of HM ship Lee July 1816

You are hereby required and directed to proceed in His Majesty’s Schooner under your command and cruise between the Isle of Anglesea, and the Lands End, and in the Bristol channel in such parts thereof as from information you may judge most proper for the prevention of smuggling that may be carried on in that district; the vessel you command is to be kept at sea as much as possible, calling at Milford for the purpose of victualling, and you are frequently to visit the different R Cruizers in that district; for list of which will accompany this and you are to report to me any appearent [sic] neglect or inattention to the public service that may be appearent [sic] in them.

You are from time to time to communicate with the officers of the Customs, and preventive boats for the purpose of giving information: and you are required to rendezvous off the Longships the first week in every month for the purpose of communicating with me at which time I expect a journal of your proceedings and the state and condition of the vessel you command. You are not on any account, to purchase stores or provisions or are you to sanction it in any of the Revenue Cruizers, but you are to afford them every assistance by supplying them with stores should it be absolutely necessary. Should you at any time receive information necessary for me or the Commander in Chief to know, you are to address me at Falmouth, and you are to report all seizures made by the vessel you command so soon after as possible.

Given under my hand on board HM Lee as from this 18th day of August 1816.

(signed) Jno Pasco Captain

The Whiting docked at the Graving Slip in Plymouth on 20 June where the copper was removed from her bottom and she was re-coppered. In July Whiting received orders to cruise the Irish Sea and was tasked with interdicting the smuggling trade from France. On the 5th August HMS Whiting left Plymouth on her final cruise.

Aground on Doom Bar

On the 15th September 1816 the Whiting made for Padstow to gain shelter from a gale and to gather information, as the ship entered the harbour close to Stepper Point a gust of wind took the schooner aback and she touched her forefoot on a sandbank. The best bower anchor was let go to hold her, the head swinging round to the north to face the harbour entrance. Advantage was taken of this by setting sail to try and sail out, but the baffling winds would not allow it and on drifting back she ran hard aground again at the stern. All boats were hoisted out, taking a cable ashore, but despite heaving for some time she would not move. The guns were moved forward to try and lift the stern and further attempts made to haul her off, but she remained stubbornly in position until at length the cable parted. It was decided to leave further efforts until the next high tide, and she lay quietly on the sandbank for some hours. As the time of high water approached it was found that she was making water, so the pumps were manned, and these soon had to be supplemented by bailing as the water rose. In the event, they were unable to control the water or haul her off.

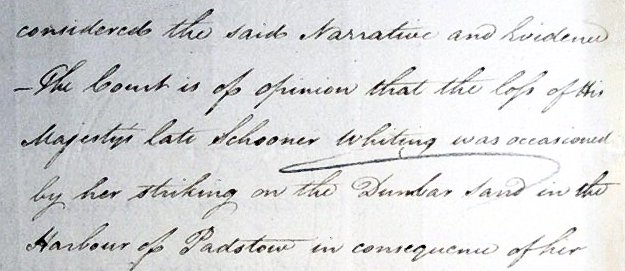

The court martial transcript from October 1816 (ADM 1/5455) provides interesting detail about her initial salvage and later abandonment:

‘16th Sept. At low water employed saving what stores could be got at. At 7 cut away the masts to ease the hull.

17th Sept. At low water people employed getting stores out of the hold and on shore.

18th Sept. At low water employed lightening the vessel as much as possible.

19th Sept. At low water employed saving all the stores possible to be got at, a party preparing slings to weigh the schooner.

20th Sept. Sent four coasting vessels down to the schooner ready to land alongside at low water on the 21st and try to weigh her.

21st Sept. Got the slings round and hove the vessel down at low water but with heavy strain. At 2 10 PM the slings gave way vessels run up the harbour people employed fitting new slings.

22nd Sept. Vessels hauled alongside again & at low water took in the ends of the new slings & hove down and when strain came on they gave way. As low water found the schooner had fallen over on her starboard bilge and to have a great quantity of sand in, and having buried herself so much, that it was impossible to sling her again.’

The wreck was abandoned and sold by the Royal Navy. Lt. Jackson was found negligent in the loss of HMS Whiting and lost one-year seniority while three crewmen were given 50 lashes with the cat 'o' nine tails for desertion.

The Padstow Petition

In 1827 the merchants of Padstow made a petition to the Admiralty (ADM 1/4985) as the wreck of the Whiting was causing an obstruction to the entrance to the harbour. The original channel was 75 fathoms wide but the effect of the wreck of the Whiting was to reduce this to 45 fathoms and to reduce the depth of the channel from 3.5 fathoms to only 2.

Any attempts to remove the wreck by the inhabitants of Padstow had failed so the merchants petitioned the Admiralty to get them to remove the wreck. The Navy responded that they had sold the wreck and could therefore not comply with the request.

The Padstow Harbour Association

In 1829 the Padstow Harbour Association for the Preservation of Life and Property from Shipwreck was formed and they proposed a scheme for assisting vessels into the harbour at Padstow. At this time the entrance through the Bar was close inshore on the west side under Stepper Point, vessels coming under the lee of the point were often taken aback by eddies in the wind. The Association proposed that a series of capstans and bollards be sited along the landward side of the entrance and a set of buoys laid on the other side of the channel allowing ships to be winched through the narrow channel. A 40 ft high tower called the Daymark was to be built on Stepper Point. This proposal is shown in a lithograph (Fig. 4) which also shows the remains of the Whiting on the Bar, still visible after 13 years.

This was a development on previous work by John Griffin who in 1761 had installed three substantial bolts and rings into the cliffs of Stepper Point that could be used for warping in ships (French 2007). The location of the rings is a key piece of information as they are mentioned by Lt Jackson during his Court Martial:

‘He sent the midshipman to make WHITING fast to the ring - the hawser parted and another was made fast - that subsequently parted resulting in WHITING bilging on her port side. When the tide next changed, WHITING was raised and then bilged on her starboard side, when the tide ebbed’.

In the 1920s the channel moved from the western side to its current position in towards the east. Part of the Harbour Association plan was to remove a section of rock from Stepper Point to minimise the wind eddies and the excavation was stated but never completed. Subsequent quarrying at Stepper Point eventually completed this task. The remains of the capstans and bollards installed by the Harbour association are still visible on the shore along Stepper Point.

Royal Navy Survey

The wreck was surveyed by C. Brown, the master of HMS Caledonia in June 1830. The report (CRO V/BO/38/6) stated that ‘excepting part of one of the stern timbers, she was entirely covered with sand’. The depth of water was from two to six feet at low water.

The report also states that ‘the sand over her is so hard, that the iron spit with which we sought for the wreck could not be driven more than one and a half foot into the sand with the whole strength of a man’. The hardness of the sand prevented any salvage work and the shallow depth of water meant that a diving bell could not be used. At this time the locals reported that the stern rail of the wreck could be visible three feet above the sand and that the hull could be walked on at low spring tide from the stern to the main hatchway. The report recommendation was to remove the exposed stern section as that was causing the obstruction but leave the main part of the wreck as ‘The removal of the whole of the wreck we are of opinion is not practicable by any means, being so deeply embedded in the sand’.

Summary

The information about the wrecking and subsequent activity provides a fairly precise location for the wreck. The later accounts describe the effect of the remains of the hull on the bathymetry of the Doom Bar and the problems it caused the merchants of Padstow. The reports state that the majority of the hull was still buried in the sand 14 years after the sinking and that the sand itself hindered any salvage attempts. At this time there is no evidence to say that the hull had been salvaged or that the hull had uncovered and eroded away or had moved so it is assumed that she remains where she was initially wrecked on the western side of the Doom Bar.