History 7: Why Was A7 Lost?

This is a condensed version, a full account of the cause of loss of HM Submarine A7 can be found in the Project Report.

Introduction

The reason was never determined why HM Submarine A7 was lost during the training exercise in January 1914. It is not certain if an inquiry was held into her loss, if it was then the report on the inquiry was not found during the extensive search through the archives. The wreck of the submarine on the seabed also provides few clues other than disproving some of the theories suggested at the time. The visible part of the pressure hull appears to be undamaged apart from three small holes which were probably caused by corrosion. The damage to the towing eye, cutwater and aft exhaust pipes are consistent with reports of damage that occurred during salvage. The main conning tower hatch and torpedo loading hatch are firmly closed so neither were left open causing the hull to flood.

A number of theories were proposed at the time the submarine was lost as to the cause of her disappearance. Some of the ideas were feasible and some fanciful but many simply highlighted the limited knowledge possessed by the general public about these secret submarines. Some of the theories include:

- The submarine was rammed

- A torpedo jammed in the torpedo tube when they made the dummy attack against Pigmy

- The submarine dived too deep, was ‘suspended’ close to the bottom and washed out to sea

- The inner torpedo tube door failed and flooded the submarine

- Petrol vapour escaped and asphyxiated the crew

- The stern fouled the bottom, damaging the propeller shaft

Taking each of the theories in turn we find that only one of them could have occurred. The area in Whitsand Bay where the exercise was being held was known to be clear of ships and the Pigmy was keeping a good lookout, so A7 could not have been in a collision with another ship. The next theory was dismissed when the submarine was relocated in 1914 as both torpedo tube doors were found to be shut. The second theory was based on the idea that seawater was more dense at depth and the submarine would ‘float’ on a deep water layer, again this was dismissed when the submarine was located not far from where she was last seen. The idea that the submarine had flooded was countered by the observation at the time she was lost that bubbles were seen to rise from the submarine at intervals, bubbles probably caused by the crew attempting to blow out ballast water, so the crew must have been alive at that time. Petrol vapour is toxic and can produce effects similar to drunkenness, and from contemporary accounts the hangover is highly unpleasant, but had this happened and the crew lost control then the naturally slightly buoyant submarine would have simply floated gently back to the surface. The last theory was that the A7 descended too deeply on her mock attack run against the Pigmy, hit the bottom and damaged her propeller; this idea cannot immediately be disproved so will be explored in more detail.

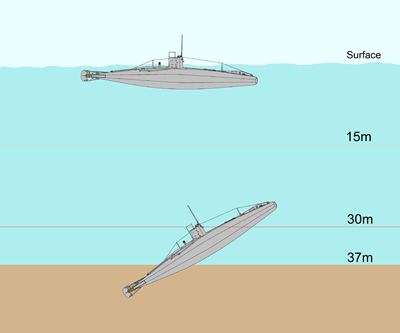

The wreck was found in 37m depth with between six and seven metres of the submarine’s stern buried in the muddy seabed and the bow 10m off the bottom, raised at an angle of 30°. Attempts were made to move the firmly embedded submarine but bad weather and a heavy swell hampered operations causing the wire hawsers passed under the hull to slip.

A7 as she was found partly buried in the seabed, also showing working depth (15m) and maximum operating depth (30m)

Capstans on the 14,000 ton battleship HMS Exmouth were used to try and pull the submarine free with a 5.5 inch hawser attached to the sub’s forward lifting eye, but this just fractured the eye plate on the submarine’s bow. Bad weather delayed salvage operation for weeks at a time. But by 25th February the salvage divers from Sheerness under Lt. Highfield had managed to get a hawser around the submarine in the hope that Exmouth could again try and pull her free of the seabed by pulling first to one side and then the other, assisted by detonating underwater charges to help shake her free. The divers hooked up the Exmouth to the hawser and she pulled for an hour and a half until the cable snapped; divers then reported that this had no effect and the submarine still had not moved. By the end of February all attempts to move the submarine had failed and on March 3rd the Admiralty ordered that the recovery operation was to be abandoned.

The Last Dive

We can now put together a sequence of events for what happened to submarine A7 on 16th January 1914. The little submarine was late leaving the dock in Devonport but it is not clear how late or what was the cause for the delay. A7 sailed down the Hamoaze then past Drakes Island into Plymouth Sound where the engine was opened to the full 12 knots in an attempt to make up lost time, but with the exercise area 17km distant it would take them at least an hour to get on site. Just past Rame Head the tender Pigmy was seen in Whitsand Bay completing her second practice run before picking up A9’s torpedo. On board A7 Welman decided to head south to try to approach his allotted position on the west side of the bay from a southerly direction. After A7 was seen rounding Rame Head it is likely that Pigmy will have sent encouraging messages to the submarine because she was so late on station. Being late for anything is never good in the Navy, but being a newly-appointed commander of a submarine and being late is much worse. Perhaps this is why Welman made the ill-fated decision not to take A7 to her allotted position but instead to start his first practice torpedo run 2 miles to the south east, in much deeper water.

Before diving, the main engine was stopped and power switched to the electric motor to maintain headway. The coxswain on the flying bridge went down the hatch, through the conning tower and in to the boat, with the captain following behind, shutting and locking the main hatch behind him. The vents were opened to the ballast tanks along with their big Kingston valves to let in water, gradually the boat lost buoyancy until the deck was awash, then the valves and vents were securely closed again. A7 motored along with just her conning tower visible above the waves and with just 600 lbs (272kg) of remaining buoyancy keeping her afloat.

_290.jpg)

White mice were used on board the boats to detect carbon monoxide, not gasoline, as they would keel over when levels got too high for their small bodies

Welman headed north using compass and periscope to guide him; he lined up for the first attack on Pigmy, keeping a watchful eye on both his target and the other submarine nearby. With the A7 now in diving trim the order was given to submerge. To counteract the small amount of buoyancy the hydroplanes on the aft end were set to 8°, the stern lifted, the bow dipped down and submarine drove smoothly underwater at between 5 and 6 knots. The watch on board Pigmy saw A7 dive at 11:10 and assumed that she was going to start her first attack run, so Pigmy carried on her straight north-westerly run across Whitsand Bay keeping a lookout for the tell-tale wake of the practice torpedo that the submarine would be firing towards them. A7 slipped beneath the waves and was not seen again.

What happened next has remained a mystery as there were no survivors from the accident, but we can now put together a likely sequence of events based on observations from Pigmy’s crew, what the divers saw when the submarine was first found and what can still be seen on the wreck today.

Pigmy saw the submarine dive, noted her position then carried on the same course across the bay. A7 still had not surfaced after 50 minutes so Pigmy’s captain decided to head back to the spot where she was last seen. On the way, the crew saw an uprush of bubbles and assumed it came from A7 in trouble on the bottom, they marked the spot with a buoy then rushed back to Plymouth to report the accident. Time was critical and at the time it was thought that the crew of the submarine only had enough air to survive for five to six hours. Around 3 hours later Pigmy was back in Whitsand Bay with a salvage lighter and a team of divers, but they failed to locate the buoy laid earlier as the waves had increased in height considerably and they were looking in the wrong location, some 1.2 miles from where the submarine lay. As night fell the ships in the search party returned to port knowing that there was now no chance of saving the crew. Pigmy’s buoy was relocated the next morning in the place where it had been dropped.

Weeks of fruitless searching then followed, starting at the last known position for the boat but with the search area eventually covering the whole of Whitsand Bay. The wreck was eventually found in 37m depth with between six and seven metres of the submarine’s stern buried in the muddy seabed and the bow 10m off the bottom, raised at an angle of 30° to 40°. So how did the submarine end up with her stern buried on the seabed?

A class submarines were of the ‘diving’ type, boats that dive by inclining their bows down by tipping up the hydroplanes on the stern. Boats of this type are inherently unstable in the fore and aft direction so that they are able to tip their bows down into the water - the problem with this method is that the submarines are more difficult to control and require an experienced crew to be able to dive safely. The A class boats were known for making sudden and unexpected dives so they needed an experienced hand to control them.

If an uncontrolled dive started there was little that could be done to bring the boat back under control because the A class submarines did not have big ballast tanks that could provide the buoyancy needed to bring the submarine to the surface quickly. An Admiralty official memorandum remarked that the principle defect of the A class was their want of buoyancy. Even so, if the electric motor was stopped while the boat was underwater the submarine should have floated back to the surface, and as we know it did not then some other event occurred to stop this from happening.

If the submarine hit the bottom then a number of factors came in to play which would compound to seal her fate. The first of these was the water depth; the Devonport submarine flotilla were usually exercised in water only 30m deep but A7 dived 2 miles south east of her assigned position where the seabed was 37m below. The operational diving depth of the A Class boats was 15m (50ft) with a maximum depth rating of just 30m (100ft). The very narrow operating range of this class did not provide a sufficient margin for error in a class of submarine that was renowned for taking unprompted dives towards the seabed. The submarine itself was also 30m long so a steep dive at the operating depth could soon put the bow of the submarine below the maximum rated depth before the dive could be brought under control.

So it seems that the most probable cause for the A7’s loss was an unfortunate sequence of events. It is likely that the boat took an uncontrolled dive towards the seabed when she first submerged, her bow was angled up at the last minute and she touched the seabed with her stern. Bows upwards but not buoyant she thrust forwards with her propeller, blowing a large hole in the soft seabed and fluidising the sand. The sinking submarine slipped backwards into the hole in the seabed she had just excavated, forcing the stern and the propeller into the sand until the propeller stalled. With the propeller no longer turning the fluidised sand in the hole settled around the hull and the mud suction held it firmly in place. This idea had been proposed in the local newspaper at the time A7 was lost: ‘…after she touched bottom an attempt was made to bring her to the surface by her own motive power, but that her propellers were already in the shifting sand, and when set in motion soon dug a hole into which she sank, and eventually became firmly embedded’.

This still leaves the question about why the A7 took an uncontrolled dive to the seabed on that cold January day. The A class boats had been in service for 10 years and the practice torpedo exercise A7 was engaged in when lost was what could be described as commonplace, in addition to innumerable diving exercises, 1,350 attacks were delivered by A boats between January 1912 and January 1914. What should have been just another routine exercise ended with the loss of eleven men. Looking at the events leading up to the loss of A7 we can see that a number of factors contributed to her loss, taken individually they were not particularly significant but when combined they proved fatal.

Unfortunate as it seems, one of the most significant factors was the inexperience of the crew of the submarine as just three of the eleven crew were experienced regulars and none of those were in senior positions. The A class boats were renowned for their instability and it was well known that they needed a firm and experienced hand on the controls to ensure a safe and controlled dive. The Inspecting Captain of Submarines stated in 1910 that, ‘it is one of the most surprising matters in under water work how very rapidly a submarine sinks and how difficult she is to check once she gains any downward momentum’. Although he had plenty of experience in A class boats, the coxswain on A7 had been away from submarines for years so it seems unusual for him to be put in charge of the boat, particularly when both the senior officers had so little experience in that craft.

The A7 was also late on station. But it is likely that there was a degree of urgency and perhaps haste in the decisions made that morning, which leads on to the second factor, that the submarine was out of position when she dived. Where A7 chose to dive the water is deeper than was usual for training exercises and the seabed is soft, sandy clay rather than the sandy gravel found in the exercise area to the north. The deeper water will have made the task of surfacing the boat much more difficult but not impossible, A class boats had been deeper and had surfaced unharmed, but being trapped by the soft seabed most probably sealed her fate.

This is a condensed version, a full account of the cause of loss of HM Submarine A7 can be found in the Project Report.

Submarine Accidents in Plymouth

Plymouth has seen more than its fair share of submarine accidents:

- The first was the sinking of the ‘submarine’ Maria in 1774, a 50 ton sloop that had been modified by the addition of an air-tight compartment. Mr John Day intended to descend in this contraption to 30m depth in Plymouth Sound hoping to benefit from wagers that he could stay underwater for 24 hours. When the attempt was made Mr Day lost his bet and became the first ever submarine fatality. This also initiated the first recorded submarine salvage attempt.

- The second occurred in 1905 when the A class submarine A8 sank in Plymouth Sound after driving herself under at speed in rough seas.

- Submarine A9 was rammed by the Little Western Steam Ship Company steamer Coath off Plymouth in February 1906. The submarine was doing a dummy attack on the cruiser Theseus when she was struck a glancing blow by the steamship which damaged the conning tower and fairing as well as bending the periscope. Fortunately the watertight shutter at the base of the conning tower was closed, a modification added after the loss of submarine A1 during an exercise, and A9 managed to surface with a conning tower full of water [Sueter, 1907, p158].

- On 10th December 1913 the submarine C14 sank in Plymouth Sound after a collision with a hopper barge; the crew escaped, no lives lost and the boat was salvaged shortly after.

- The most recent was in January 1914 when the A7 was lost in Whitsand Bay.

_300.jpg)