Not Set

The early Royal Navy A class submarine was lost with all hands during a training exercise in Whitsand Bay, Cornwall, on 16th January 1914.

Type

Royal Navy A Class submarine

History

The A7 was a Royal Navy A-Class coastal submarine that was laid down in September 1903 and completed in April 1905 as part of the Group II programme that included submarines A5 to A14. Like all her class, she was built by Vickers in Barrow-In-Furness as a joint development between the company and the Admiralty, as the technology was new and the A class were the first British-designed submarines in the Royal Navy. The A7 was 30.2m (99ft) long with a beam of 3.9m (12ft 9in) and a draft of 3m (10ft) and displaced 207 tons submerged. On the surface, she was powered by a specially designed 500 BHP 16-cylinder Wolseley petrol engine and submerged she was powered by a 150 HP electric motor fed by a large bank of batteries.

At 8 a.m. on the 16th January 1914, the A7 proceeded to sea with the 25-year-old Cornishman Lt. Wellman in command, in company with the depot ship HMS Onyx, the tender Pygmy and five other submarines. Once in Whitsand Bay, the submarines ran a series of dummy attacks against the surface ships. At 11:10, the Pygmy started her next run in front of A7, and the submarine dived to attack. Nothing more was seen of the A7, so Pygmy sailed back towards where the submarine was last seen, but there was no sign of her. The last known location was marked with a buoy, then Pygmy returned to Devonport to report the A7 missing. A message was sent to Sheerness requesting that Yard Craft No. 94 be sent to assist, as she had been successful in raising the submarine C14 from Plymouth Sound in the previous December. Unfortunately, by the time the tugs arrived at the place where the A7 sank, the buoy dropped by Pygmy could not be found, so the rescue ships had no clue about the location of the sunken submarine.

By this time, there was no hope for the crew, but A7 needed to be salvaged to see what went wrong. Twelve torpedo boats and destroyers were engaged in searching for the submarine using wire sweeps, supported by divers to identify any objects detected on the seabed. By Tuesday 20th, there were sixteen ships working in pairs sweeping the seabed with wire hawsers, trying to snag the submarine, hampered by fog, bitterly cold winds and rising seas. Each snag had to be investigated by a diver, and the only thing they had caught were large rocks. By now, Yard Craft No. 94 had arrived in Plymouth from Sheerness, but she could do nothing to help until the submarine had been found. Two more snags had been located the evening before and as it was too late for divers to work, the snags were marked with buoys and a destroyer anchored by each one. Diving operations resumed in the morning but to everyone’s disappointment, they were both found to be rocks.

It took many days of searching before the submarine was discovered as the area they had to search was very large. Finally, on Thursday 22nd, the submarine was found. The crew of the Pygmy, the vessel involved in the original training exercise, spotted a large quantity of oil floating on the sea. They sent down a diver who soon confirmed that they had finally found the A7 only a short distance from where the Pygmy had last seen her.

The wreck was found in 36m depth with between six and seven metres of the submarine’s stern buried in the muddy seabed and the bow 10m off the bottom, raised at an angle of 30°. Attempts were made to move the firmly embedded submarine, but bad weather and a heavy swell hampered operations, causing the wire hawsers passed under the hull to slip. Capstans on the 14,000-ton battleship HMS Exmouth were used to try and pull the submarine free with a 5.5 inch hawser attached to the sub’s forward lifting eye, but this just fractured the eye plate on the submarine’s bow. Bad weather delayed salvage operation for weeks at a time, but by 25th February the salvage divers from Sheerness under Lt. Highfield had managed to get a hawser around the submarine in the hope that Exmouth could again try and pull her free of the seabed by pulling first to one side and then the other, assisted by detonating underwater charges to help shake her free. The divers hooked up the Exmouth to the hawser, and she pulled for an hour and a half until the cable snapped. Divers then reported that this had no effect, and the submarine still had not moved. By the end of February, all attempts to move the submarine had failed, and on 3rd March the Admiralty ordered that the recovery operation was to be abandoned.

In the 1970s, there was a known fastener reported by fishermen in the area where the A7 was lost. The submarine was first visited by sports divers in the 1980s and was identified by Navy clearance divers in 1985 as the lost submarine A7. She was found intact and buried in mud up to the waterline with her deck 1m clear of the seabed, periscope extended, hatches closed, and a small hole in her starboard side. The site was then occasionally visited by divers, but being small and in deep water, she was hard to find. In 1999, the police found the compass binnacle from the A7 in the possession of a local diver; he was given a caution, and the binnacle was recovered and given to the Submarine Museum in Gosport. In 2001 the Ministry of Defence added 16 wrecks, including the A7, to a list of controlled sites under the Protection of Military Remains Act, so now the site can only be dived with permission and since then permission has never been granted.

See the A7 Project web site for the full story of HMS/M A7

The A7 Project in 2014

The aim of the A7 Project was to investigate the Royal Navy submarine HMS/M A7 lost in Whitsand Bay, Cornwall, in 1914. The project was a wide-ranging study into the development, the loss and the current condition of the submarine.

Prior to its designation in 2001 the A7 was rarely visited by sports divers due to the difficulty of locating the small submarine in deep water and the nearby presence of more accessible shipwrecks. Consequently little is known of the wreck site, its environment and how the submarine has deteriorated over time. Similarly the history of the vessel and its loss has received scant attention either in the historical or educational record, either locally or nationally. Since its designation as a Controlled Site no monitoring has been conducted on the site and since no baseline survey was ever conducted it is impossible to tell whether or at what time any unauthorised physical interference has occurred. There was much that could be learned so in 2013 the A7 Project was created by the SHIPS Project team.

The project started in October 2013 with a proposal put to the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) to undertake an archaeological investigation of the submarine. The A7 is a Controlled site under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 and unauthorised access to the site is prohibited. The project proposal was accepted by the MoD and the first license to visit a Controlled site was issued to the SHIPS Project for a two month fieldwork season in the summer of 2014.

See the A7 Project web site for the full story of HMS/M A7

The remains of the A7 submarine are still largely intact so the undocumented secrets of how this submarine was constructed and operated still remain a mystery. But the hull is corroding and this project suggests that a conservative estimate for the survival of the hull to be between 40 to 50 years. The significance and rate of deterioration of the A7 have led to proposals in this report for further work on the site including monitoring change during annual site visits, further corrosion studies and more detailed recording of the unique features of the submarine.

The results of the A7 Project was published in a 120 page report by BAR Publishing, click here for details ![]() .

.

.jpg)

Multibeam image of the SS Rosehill wreck site, click the image for a larger version [University of Plymouth]

Location and Access

Whitsand Bay, Cornwall

This vessel contains the remains of its crew and as such is a controlled site under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 and therefore requires a licence to be granted before visiting the site.

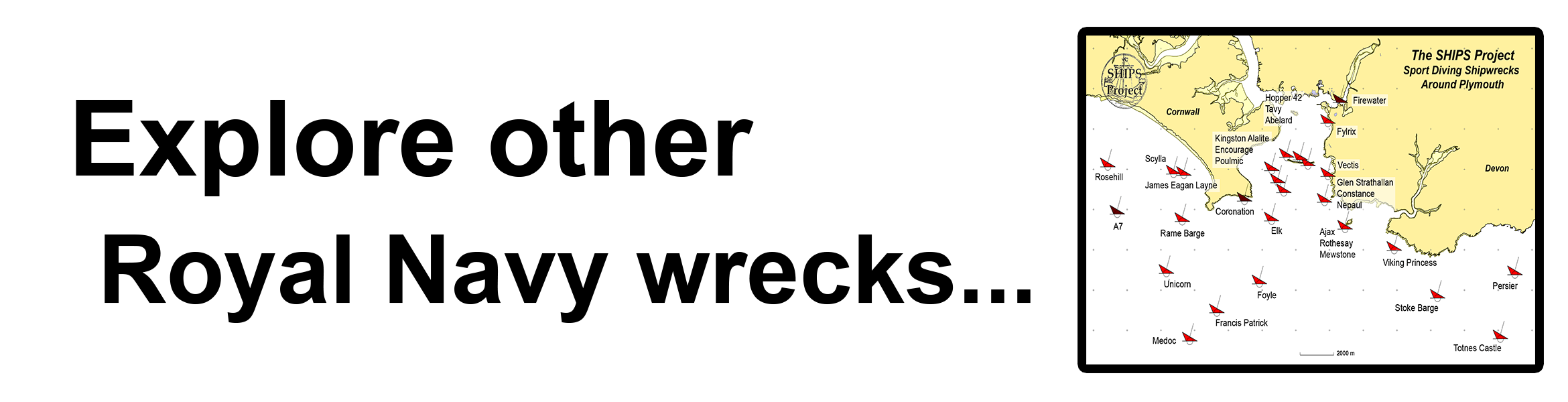

Nearby wrecks include the James Eagan Layne ![]() , Rosehill

, Rosehill ![]() , the Rame Barge / Leen

, the Rame Barge / Leen ![]() and HMS Scylla

and HMS Scylla ![]()

Last updated 27 June 2025

Information

Date Built:

1905

Type:

Royal Navy A class submarine

Builder:

Vickers, Barrow

Owners:

Royal Navy

Official Number:

A7

Length

30.2m (99ft)

Beam

3.9m (12ft 9in)

Draft

3m (10ft)

Construction

Wrought iron

Propulsion

Petrol, Wolseley

Displacement

207 tons

Armament

2 x 18in torpedoes

Master

Lt. Gilbert M. Welman

Crew

11

Portmarks

None

Date of Loss

16th January 1914

Manner of Loss

Trapped

Outcome

Abandoned

Reference

NMR 919768, UKHO 17645

.

Not Set

Leave a message

Your email address will not be published.

Click the images for a larger version

Image use policy

Our images can be used under a CC attribution non-commercial licence (unless stated otherwise).

![Drawing of HM Submarine A7 [SHIPS Project]](../images/Wrecks/SHIPS_Wk_A7 (9).png)

![Features on HM Submarine A7 [SHIPS Project]](../images/Wrecks/SHIPS_Wk_A7 (10).jpg)

![Features on HM Submarine A7 [SHIPS Project]](../images/Wrecks/SHIPS_Wk_A7 (11).png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)