Not Set

A ship possibly associated with the West Africa slave trade was wrecked at the north end of Plymouth Sound and its remains are being investigated by The SHIPS Project.

Type

Armed merchant ship, mid to late 17th century.

Location

The site is near an isolated shoal now called Asia, at the northern end of Plymouth Sound in South Devon, England. To the north of the site lies the main deep-water channel that runs east-west across the top of Plymouth Sound, which is also the confluence of the river Tamar and the smaller river Plym. The shallow rocky knoll lies on the edge of an area of shallow water between the Knoll and Drake’s Island to the west called Asia Shoal. To the east of Asia Shoal is a deeper water channel running north-south called Asia Pass. Further to the east lies Winter Shoal, a more prominent area of shallow water, then east again lies the main shipping channel into the Cattewater and the Hamoaze, bordered by another shoal called Mallard. Sailing ships entering or leaving the entrance to the Plym known as the Cattewater or the lower reaches of the Tamar known as the Hamoaze may pass Asia Knoll depending on wind conditions.

The Asia Knoll shipwreck is close to the old sailing ship anchorage on the north side of Drake’s Island, a location often referred to on older documents as ‘between the Island and the Main’. The island provided shelter from southerly winds to ships lying in this anchorage and the holding ground was good. However, any ships that dragged their anchors would have very little time to recover before being wrecked as the mainland shore lay close in all directions. There are many accounts of ships at anchor in Plymouth Sound dragging their anchors northwards in a storm as the prevailing winds are from the southwest. Many ships have been wrecked under the Hoe at the northern end of Plymouth Sound and even more have been lost on the promontory of Mount Batten and in Jennycliff Bay to the northeast. The shallow Asia, Winter, and Mallard shoals were also a hazard to any anchored ships dragging their anchors northwards in storm conditions.

Site History

The Asia Shoal shipwreck has been visited by sport divers for decades as it provided shallow, sheltered water for diver training, the site could be dived when the sea was too rough to dive elsewhere, and it was only a short distance from a launch site which was important when dive boats were small and slow. The site was originally accessed by going down the Asia Shoal buoy chain which used to be moored much closer to the shoal. The buoy marked the edge of the shipping channel so there was always the risk to divers of a large ship passing close by.

In the 1990s, six copper manillas were recovered by a local diver from the top of Asia Knoll and now since lost while one single manilla was found by another diver which is still in his possession and has been recorded by The SHIPS Project.

In the first half of 2003, Associated British Ports announced plans to invest in excess of £4 million at Plymouth, in preparation for the arrival of Brittany Ferries’ new super ferry, the Pont Aven, which would begin regular sailings from Plymouth’s Millbay Docks in the spring of 2004. The works include capital dredging and as part of this work, ABP planned to remove the shallow rock outcrop at Asia Knoll to improve access to Millbay for the ferry. The environmental impact assessment that has to be done before dredging can start was facilitated by discussions with Plymouth City Council Historical Environment on 14th April 2003. The ABP Environmental Statement does include impacts to archaeological features but for some reason is limited to Millbay Docks and the impact of the dredging at Asia Knoll is not mentioned at all. No geophysical or underwater surveys were done to establish if there were any shipwrecks in the area to be dredged so a large part of this shipwreck site was dredged away and dumped at sea when Asia Knoll was removed.

The site was dived by The SHIPS Project in 2018 to assess its potential and three cannon were relocated, this was followed by more investigations where more cannons, an anchor, pottery, a lead ingot, and ship’s rigging were found. The SHIPS team also relocated an early aircraft engine and possible aircraft parts that had been reported as being on the site, see Asia Knoll Engine ![]() . The team have also completed multibeam sonar, side scan sonar and magnetometer surveys of the site working with the University of Plymouth and Sonardyne International Ltd. Further work is on-going with the SHIPS team's professional maritime archaeologists working with volunteers from local sports diving clubs including Plymouth Sound BSAC and Totnes BSAC.

. The team have also completed multibeam sonar, side scan sonar and magnetometer surveys of the site working with the University of Plymouth and Sonardyne International Ltd. Further work is on-going with the SHIPS team's professional maritime archaeologists working with volunteers from local sports diving clubs including Plymouth Sound BSAC and Totnes BSAC.

Objects found on Site

Manillas

This object is the sole surviving example of seven manillas recovered from this site. A manilla is a horseshoe shaped circlet of copper alloy with flattened and thickened ends. Manillas were commodity money often associated with the transatlantic slave trade, also known as Okpoho which is the word for money in the Efik language.

Single manilla (10A07) recovered from the now dredged area of Asia Knoll, six other manillas (11A28) were taken by a local diver from a similar location on a different date, but subsequently lost. This example is 88mm long by 82mm wide, 9mm diameter at the thinnest point, flat face 23mm x 19mm, gap 27mm to 40mm at the widest point and weighs 197g (6.95oz). Chemical analysis shows that this manilla is almost entirely copper with a few trace impurities. This manilla is the same length and same minimum thickness, but more rounded and heavier than the nine manillas found on the late 17th century shipwreck Site 35F in the English Channel. The manilla is also similar in size and form to those found on the Elmina Wreck, a mid-seventeenth century shipwreck, which archaeological and archival research suggests is the Dutch West India Company vessel Groeningen that sank after arriving at Elmina on a trading voyage in 1647.

It has been suggested that the first manillas were made from copper pins salvaged from European shipwrecks however the use of manillas in West Africa predates the use of copper fastenings in European trade ships. Vasco da Gama in 1498 on his first voyage noted their use in Southern Africa, took trade goods the same as overland routes, noting ‘Copper seems to be plentiful, for the people wore (ornaments) of it on their legs and arms and in their twisted hair’ (Ravenstein 1898). It seems that manillas were the favoured form of currency from the start of mercantile trade with West Africa. The merchant ship Paul on a voyage to Brazil via West Africa in 1540 took 940 hatchets, 940 combs, 375 knives, 10 cwt (508kg) of copper and lead arm bands, 10 cwt (508kg) lead in the lump, 3 pieces of woollen cloth and 19 dozen nightcaps.

Copper and brass goods were an important constituent of slave trade cargoes, commonly the second most valuable after textiles. Hundreds of thousands of manillas were shipped from Europe to Africa as trade goods, many manufactured in foundries in Birmingham, and as late as 1855 it was reported that Birmingham had cast more than 300 tons of manillas. Many manillas available for sale in the UK come from a shipwreck in the Isles of Scilly thought to be the snow Douro. At only 50mm long the Scilly manillas are much smaller than the ones found in Plymouth and are made from copper heavily debased with 20% tin, 6% lead and 3% iron, and were probably made in Birmingham.

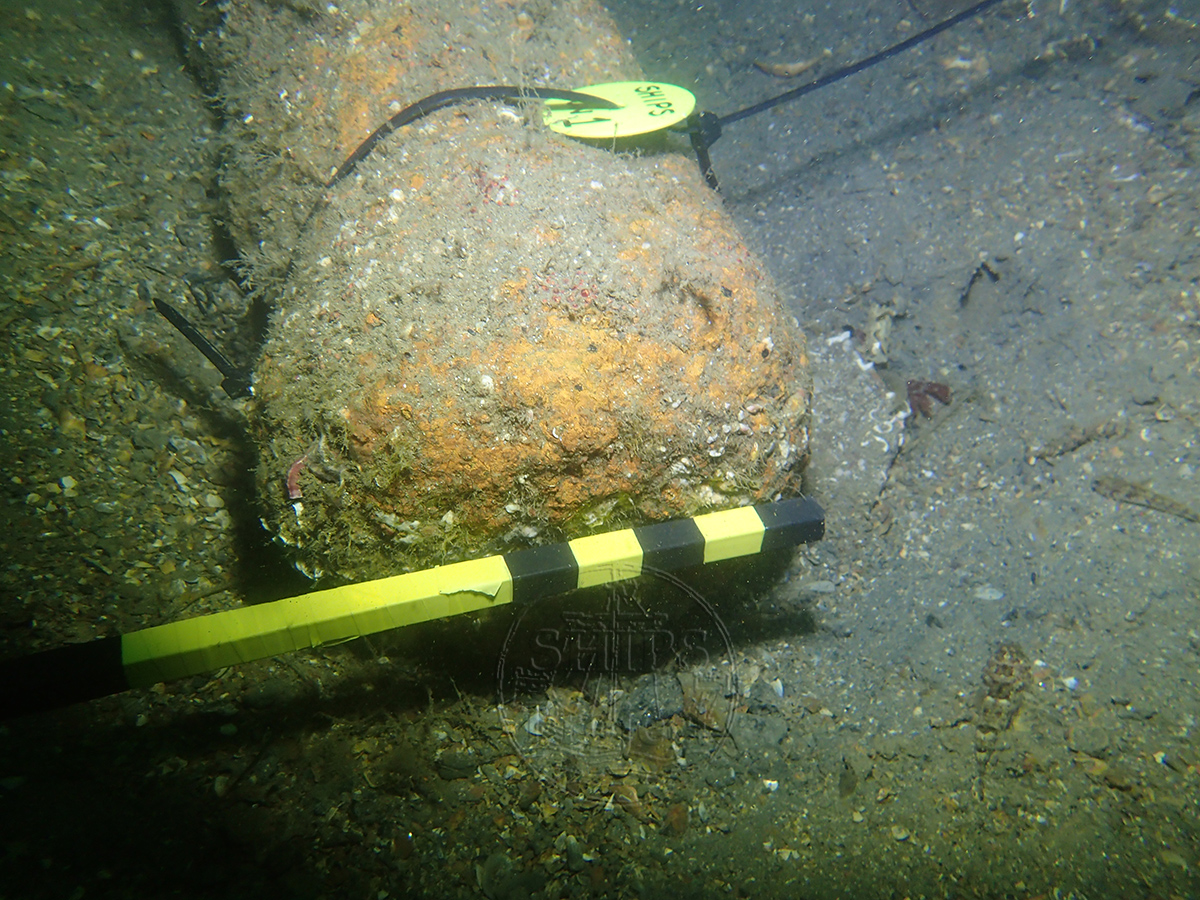

Cannons

Four small cannons (guns) can be found on the seabed on the site, they are all about 1.3m (4ft 4in) with a base ring diameter of 220-250mm (8.7-9.8in). All the guns are heavily eroded and covered in thick concretion with rocks and iron objects concreted to some of them. One gun was raised from the site and moved to the breakwater at Queen Anne's Battery in the Cattwater while another was raised by Exeter BSAC diving club and its whereabouts are unknown. The guns are very small; an accurate bore measurement has not been possible so far, but it is estimated that they would fire a shot of either 1lb (2in bore) to 2lb (2.5in bore).

Ship's Rigging

This heart block (18A28) was excavated from soft sediment when the site was first investigated. This is a heart block, a block without a sheave which was part of the standing rigging on the ship used in pairs to join a mast stay to a collar around a mast, with lanyards to provide the tension between the blocks. The stay or collar would be fitted around the outside of the block, in this case with a single turn and the large hole in the centre is chamfered to take the lanyards. The rope around the outside of the block would be approximately 100mm (4in) in diameter.

A wooden sheave (22A09) that was part of a rigging block was found on the shipwreck site. The sheave is 190mm in diameter and 30mm thick and is made from the heavy timber, probably lignum vitae. The sheave would have once had a metal fitting in the hole in the centre called a 'coak', most probably copper alloy. Many sheaves and coaks have been found in Plymouth Sound and The SHIPS Project have recorded some of them. Most have been from 18th and 19th century ships of the Royal Navy which use distinctive forms for their coaks. The sheave found on the Asia shipwreck would have had a coak cast as a single piece in an unusual form comprising an octagonal body 50mm A/F and 22mm thick attached to the sheave with two fasteners through a larger six-sided section . To date we have not been able to identify a similar sheave fitted with this type of coak.

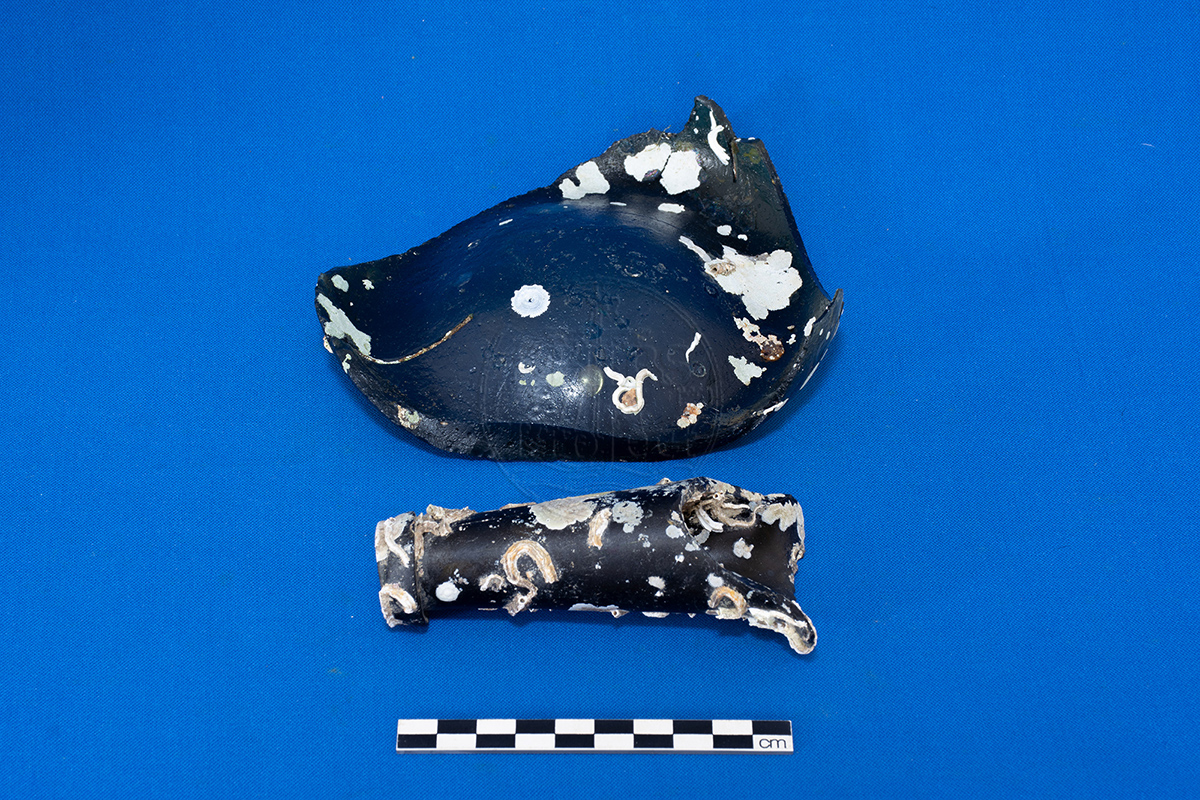

Pottery

Pottery found on the site includes pieces of Bartmann or Bellarmine jar. Bartmann jugs are a type of salt glazed stoneware manufactured in the Rhineland in the 16th and 17th century, particularly from Cologne and Frechen. By the early 17th century there were large exports from the region to England, with stoneware jugs and bottles shipped across the channel by the thousands. One of the pieces includes a medallion from the belly of the jar (18A41).

The medallion depicts a bearded, long-haired man standing with arms outstretched in Elizabethan dress, wearing doublet, breeches, hose, ruff, and codpiece. On one side is a depiction of a house, on the other is a plant and between his legs is a flower. In one hand he may be holding a jug and in the other a goblet. The text over his head is mostly missing and not clearly discernible but appears to be ‘HIE. T____EIT’. The design on the medallion is unusual with only one similar piece located so far and that has been dated by the Bellarmine Museum to 1580-1600.

Other Objects

A small lead ingot was found on the wreck. The ingot has straight, flat sides, no markings, and was cast in a vertical mould with remains of the casting sprue is visible at one end. This ingot is similar in design to the larger silver ingots recovered from the VOC ship Rooswijk (1739). This ingot is unusual because of its size and shape. In the 18th Century lead as cargo was transported in large boat shaped ingots or in rolls of thin sheet. Ships often carried lead in rolls to use as 'tingles' or patches for repairing leaks or to make protective coverings. This ingot is unusual as it is so small and so well made, it appears to be cast in a parallel sided vertical mould which would be more time consuming and expensive than the more usual open topped boat-shaped moulds.

The Asia Knoll Shipwreck

Asia or 'Africa' Knoll

The names of places in Plymouth Sound have changed many times over the years. For example, Drake’s Island is shown on charts to be St. Nicholas’ Island up until 1782 and the stretch of water known today as the Cattewater was only given that name in the late 1800s, before that it was known as the Catwater.

The shoal currently called Asia also had a name change, as charts from 1798 and 1817 refer to it as ‘Africa’. This shoal is not mentioned on many early charts as the nearby and shallower Winter Shoal is shown instead. The 1798 Heather chart is one of the first to show the shoal and here it is called ‘Africa’. The 1809 chart by Chapman calls it ‘Asia’ and a chart from 1817 refers to it as ‘Africa’. Where later charts show the shoal, it is called ‘Asia’. There is no record of why the shoals have the names they do other than Shovell Rock, as Sir Cloudesley Shovell ordered a buoy to be put on it. One suggestion is that the shoals are named after Royal Navy ships that hit them, or perhaps discovered them. Panther Shoal may be named after HMS Panther as there has been a ship of that name from 1703 onwards, but the names of Tinker, Knap, Mallard, and Winter shoals may have other origins. There has been an HMS Asia since 1694 and an HMS Africa from the same date so the shoal could be named after them. It also does not take a stretch of the imagination to think that the shoal was named after a ship of the Africa trade that wrecked on it, there is no evidence for this as yet but research into the origin of place names is ongoing.

The Slave Trade and Plymouth

In 1562, Sir John Hawkins sailed from Plymouth in England to Guinea in the west coast of Africa on the first English slave trading voyage. This was not the first slaving expedition to that region by Europeans, that had occurred a century earlier by the Portuguese who were the first to explore the coast of Africa by sea and the first Europeans to sail into the Indian Ocean. Trade to the west coast of Africa gradually increased with goods manufactured in England such as textiles and copper were shipped to Africa, the goods were traded for slaves which were then taken to the Americas, with raw materials such as sugar, cotton and tobacco brought back from the Americas on the return journey in what became known as the triangular trade. There was also two-way traffic from Europe to Africa, from Africa to the Americas and from the Americas to Europe and not all trading voyages to west Africa involved the purchase of slaves. Plymouth was not suited as a base for voyages to west Africa as it was not supported by a large manufacturing base and had no facilities for processing raw materials such as tobacco and sugar brought back from the plantations in America. Instead of Plymouth, the ports of London and Bristol and then Liverpool became the centres of the slave trade in England; from 1750 to 1807 Liverpool was the largest slaving port in the world. Only a small number of ships left Plymouth on slave trading voyages during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, some left from Plymouth while others stopped for supplies or repairs after having departed from another port.

Interpreting the Site

So far there is little hard evidence about the type of ship that wrecked on Asia Knoll but the investigation has only just started. The ship was probably associated with the West Africa trade because of the presence of manillas on board, and the ship could have been involved in the slave trade because the West Africa trade was dominated by slaving. However, it is hard to prove that a ship was involved in transporting slaves unless manacles and other slave equipment are found on the wreck, but this was only fitted during the middle passage from Africa to the New World. The wreck of a slave ship in UK waters would look very much like any other merchant vessel from that time.

The objects found so far suggests that the shipwreck dates from the mid to the late 17th Century (1650-1700) and is a merchant ship armed with at least six guns, that may have been associated with the West Africa trade.

Location and Access

Permission to dive the site must be obtained from Queen’s Harbour Master, Plymouth, as the wreck lies inside the main shipping channel.

Last updated 18 April 2022

Information

Type:

Armed merchantman

Date Built:

Unknown

Date of Loss:

Unknown

Manner of Loss:

Wrecked

Outcome

Abandoned

Builder:

Unknown

Official Number:

None

Length

Unknown

Beam

Unknown

Depth in Hold

Unknown

Construction

Timber

Propulsion

Sail

Tonnage

Unknown

Nationality

Unknown

Armament

More than 6 cannons

Crew

Unknown

Master

None

Owner

Unknown

Reference

None

.

Not Set

Leave a message

Your email address will not be published.

Click the images for a larger version

Image use policy

Our images can be used under a CC attribution non-commercial licence (unless stated otherwise).