The Origins of Plymouth

The sheltered waters of Sutton Pool in Plymouth were formed when the sea broke through a narrow limestone ridge that joined the high ground of Plymouth Hoe in the west with the lower Teat’s Hill to the east. Sea level was once much lower, and at that time, the shallow freshwater pool north of the limestone ridge was fed by two small streams. The overspill from the rivers flowed out through a narrow gap in the rocks to join the main river Plym, in what would eventually be called the Cattewater. The freshwater pool had arms extending westward under what is now the Barbican Parade, northward toward where a Friary would be built and westward towards the river Plym along what is now the reclaimed land of Gdynia Way. Sea level rose over time, eventually flooding Plymouth Sound and the estuaries of its two main rivers, the Tamar and the Plym, making Sutton Pool a tidal inlet. The waters of Sutton Pool were originally much larger in area than they are today, and the edges of the Pool were fringed with sandy beaches and rock outcrops on the west side and mud on the eastern shore.

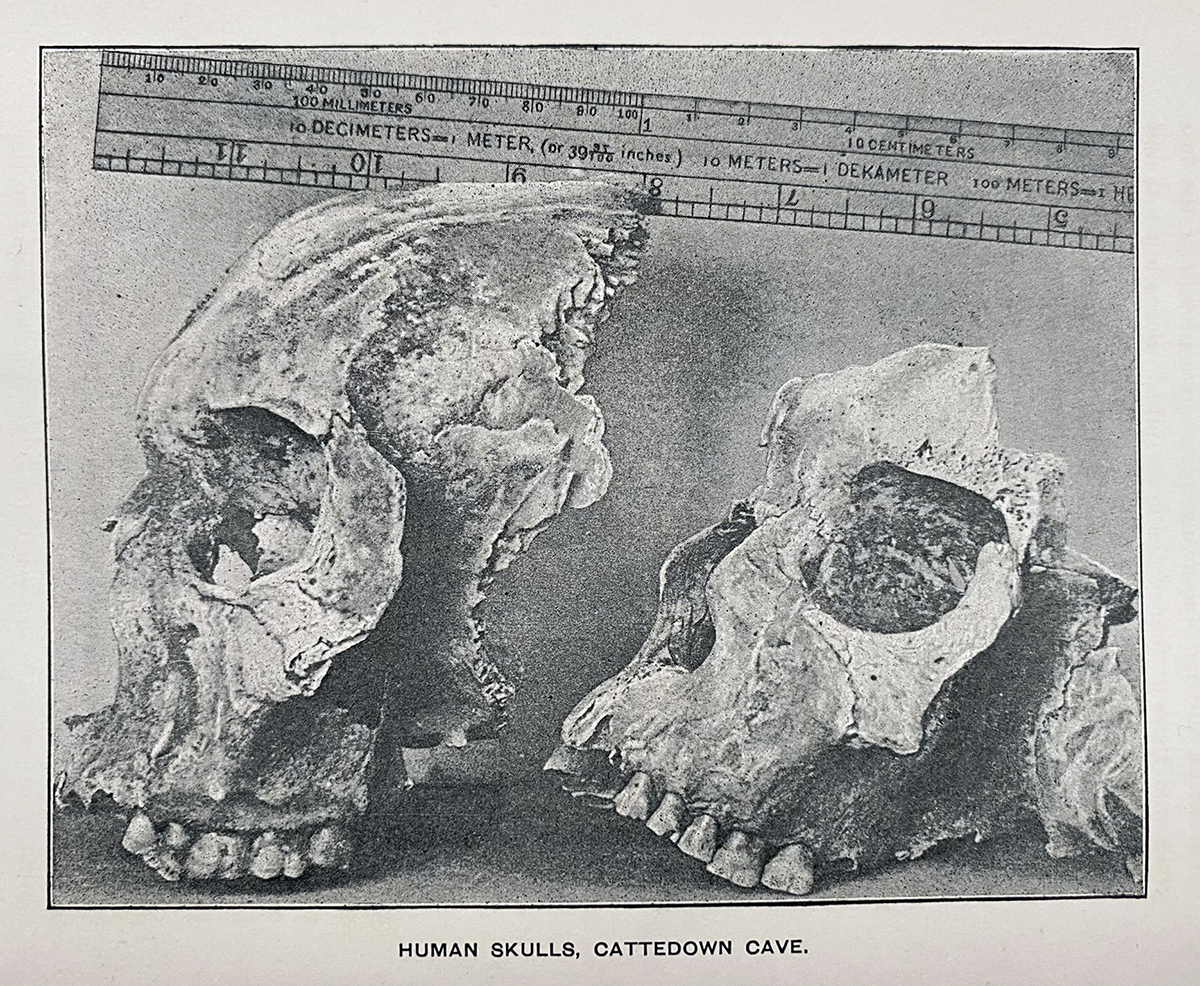

People have lived in the area now called Plymouth for thousands of years; Cattedown was occupied after the last Ice Age. Mount Batten was a Bronze Age port where foreign visitors would come to Plymouth to trade, but would leave little evidence other than a few lost ships’ anchors made of stone. The Romans came to Plymouth Sound, also leaving anchors, but these were made of lead. They also left their pottery and coins, and they left broken fragments of roof tile under buildings in Woolster Street alongside Sutton Pool (Note 1). Some of these early inhabitants buried their dead near Sutton Pool; an early burial site was discovered at Stillman Street in the Barbican, just 50m inland from what was the foreshore at that time. Like today, these first occupants found Sutton Pool an attractive place to live. There is fresh drinking water from the streams that fed the Pool, protection from prevailing south-westerly winds provided by Plymouth Hoe, and abundant seafood to be found in Plymouth Sound. At the time, the Hoe was a barren limestone ridge covered with gorse, scrub, and rough pasture, with cliffs on its southern side dropping into the sea, but it was a good lookout where trading ships could be seen entering Plymouth Sound. Tracks were made around the edge on the rocky western side of the Pool, perhaps out to Fisher’s Nose along the shoreline to go fishing. Hints of these ancient trackways can be seen today in the alignment of the flat and level roads in the Barbican. Land was later reclaimed from the Pool between these tracks and the foreshore, creating more room for quays to serve the ships using the harbour.

Culturally, the first people in the area were Celtic, as this was originally part of the ancient Kingdom of Dumnonia. Their culture was different from tribes further east, and it had more in common with other Celtic tribes to the north and south, along a route for trade and cultural exchange that ran from Scotland down to the north of Spain. When the Romans arrived, Dumnonia stretched from Land’s End in the west to the Blackdown Hills east of Exeter, in what is now the modern counties of Devon and Cornwall. The Romans came to the southwest and built a legionary fortress at Exeter, a smaller temporary fort at Calstock on the River Tamar, and a string of smaller forts down through the middle of Cornwall. The Romans did not stay long, so the social and economic system developed by the Dumnonii remained largely unchanged. Perhaps this was a deliberate decision to reject the Roman way of life, which is in sharp contrast to the rest of Romanised Britain to the east.

Following the end of Roman authority in Britain in the early fifth century, the original native kingdoms re-emerged. The Dumnonii expanded their territory eastwards after the Romans left, but it contracted later as the next in the series of invaders, the Saxons, advanced westwards. Between 710 and the early 9th Century the Anglo Saxon Kingdom of Wessex expanded across Devon, probably arriving at the Tamar around 813 when King Ecgbert 'laid waste the West Welsh (southwest Britons)' from East to West. However later battles at Gafulford, possibly near Lew Trenchard, and Hingston Down, possibly Hingston Hill on Southern Dartmoor, show the Britons remained independent West of the Tamar. This decision to leave the Dumnonii undefeated and allow self-rule had lasting repercussions. This independence was honoured by many later English rulers. Cnut did not extend his laws into Celtic-speaking Cornwall, and Henry I treated Cornwall separately from the rest of his realm. William the Conqueror was smart enough to place lords in Cornwall who were acceptable to the inhabitants; if they had to have a lord, then at least they had a lord they accepted. The Dumnonii tribe that became the Cornish are remarkable in that they appear to have remained separate from the many invasions and power struggles that England was subjected to for thousands of years. They tolerated the Romans, were tolerated by the Saxons, welcomed the Vikings and were cossetted by the Normans. This separate treatment of Cornwall eventually led to the Duchy of Cornwall Charters of 1337-38 and is the cause of Cornwall’s peculiar and unique constitutional position today.

Echoes of this unique treatment may explain some of the events relating to the story of Plymouth’s early defences. The line of separation between Celtic and non-Celtic land is not well defined and has changed over time, but it resulted in Plymouth always being in border country. Being on a border often gives the residents a rather philosophical attitude toward kings and lords; allegiances could switch overnight so long as their daily life was not affected. This may help explain the independent attitude of the citizens of Plymouth who always looked after their own interests, whichever king or overlord happened to be in power at the time.

Note 1. The 118 Roman roof tile fragments were identified as coming from a building on the Woolster Street site. Only fragments of tiles were found and of two distinct types, so the pieces may be waste from cargo ships that unloaded tiles on the foreshore. There are similar waste tips of ceramic cargoes on the foreshore in other locations in the Tamar waterway.

Leave a message

Your email address will not be published.

Click the images for a larger version

Image use policy

Our images can be used under a CC attribution non-commercial licence (unless stated otherwise).